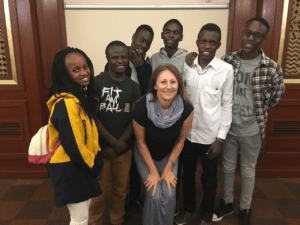

Kirsten Hanna (white shirt) and Ashley Goolsby (blue shirt) made the trip earlier this year to Shelter Children’s Home in Africa. In small ways, the two local residents are helping sustain the orphanage.

By SARAH DOOLITTLE, Four Points News

After visiting an orphanage in Ngong, Kenya, two Four Points neighbors decided to make it their mission to help.

In January, Kirsten Hanna and Ashley Goolsby visited Shelter Children’s Home, the orphanage and school is home to 151 Kenyan boys and girls, from newborns through their late teens, and boasts over 300 alumni.

Goolsby — who owns restaurant Shack 512 on Lake Travis with her husband — had visited previously and was sponsoring the cost of one student’s college education at the home. Timing was right, their son Gray graduated Vandegrift in 2016.

“She and other people have, over time, helped the orphanage a lot financially,” Hanna explained. She originally balked at the idea of leaving behind her husband and three children to visit the African orphanage. She had never been to Europe much less Africa.

“Africa? That’s so different, so far removed, nothing I ever thought I would ever do,” said Hanna, who is a real estate agent with Nest Properties Austin and lives in Preserve at Four Points.

Africa trip

Still, the idea gained momentum as she realized the possibility of being able to help. Hanna and Goolsby traveled to Kenya with a group of five women from around the U.S. They spent three days at Shelter then one day in Eldoret, Kenya meeting with street boys and moms.

“It was a very eye-opening and emotionally exhausting several days,” said Hanna. “It made us stop and really put our lives into perspective.”

She did not know what to expect at the orphanage but did have some preconceptions that proved to be false.

“I figured I was going to go there and everybody was going to be miserable because nobody has anything in Africa,” Hanna said.

Instead she came to the realization that, “Nobody needs any of these things.” Kids she met at the home took pleasure in simple things, like a foam craft project the group had brought to share.

The group also met Mary Wambui Muirvri, who runs the home and is “Mom” to all its residents.

Muirvri came to Austin to visit Hanna and Goolsby in the spring and Four Points News interviewed her then.

Orphanage

It was Muirvri’s grandmother who started the orphanage in 1997 as a place for impoverished women. “My late grandmother… had a great passion to help the poor women living in the slums,” Muirvri said. Nairobi is home to the largest urban slum in Africa.

Muirvri grew up working in the home and later studied accounting. After graduation, she worked in her field earning an income for her family. Muirvri and her husband had two children at the time.

But as with so many destinies, Muirvri was as yet unaware — and unwilling — that hers would be tied to this place. “(My grandmother) sold this idea to me slowly as I resisted it.”

“She left the mantle to me,” when her grandmother then died in 2000, “and I thought this was the worst nightmare. I had no clue what to do or how to do it.”

Determination and faith slowly transformed her fears, and Muirvri now knows this is life she was meant to lead.

“Despite the fact that this project is difficult to run, I feel blessed. Seeing the orphans — abused, neglected and vulnerable children — acquire a quality education for self-reliance is my greatest joy,” she said.

Four Points visit

Muirvri has also waged a personal campaign against female genital mutilation, and her work has not gone unnoticed. In March, she was invited by the United Nations to visit New York to speak on the topic.

Knowing Muirvri was coming to the U.S. for the first time, Hanna and Goolsby invited her to make a trip to Texas in April on her way to California where she had also been invited to speak at the Hoover Institution, a public policy think tank at Stanford University.

Hanna and Goolsby loved the opportunity to host their new friend, each for two days, and to give her a taste of life in Four Points.

For Hanna’s daughter, Emily, “I was a little nervous about meeting her,” being acutely aware of the difference in their two lives. “(But) she is the most heartwarming person to be around.”

Hanna especially enjoyed Muirvri’s reaction to the family’s hot tub.

“I asked her if she wanted to go in the hot tub… So she borrowed a swimming suit. Then the next day she asked, ‘Can we go back in that hot bath?’ So cute. She didn’t want to get out,” Hanna said.

As for Muirvri, “I had a great experience in your beautiful, very clean country.” She noted that the U.S. has a lot of available food, that everyone works hard and there are no old cars on the roads. “(And) you can get everything you need in one store.”

“While Mary was in Austin with us, she commented continually on our abundance of food we have here and even asked us why in the world we would ever want to leave and go to Africa,” Goolsby said. “My answer was easy… If we in some small way can change these children’s lives… Isn’t that what we were put here on earth to do?”

Shelter’s future

While Kenya is a beautiful country renowned for its wildlife, it faces many of the challenges borne by multiple developing countries in Africa. The lack of a social safety net, migration to cities from rural areas for jobs, HIV/AIDS, sexual abuse by relatives and female genital mutilation by the Maasai have all contributed to the burgeoning orphan population.

In addition to providing a safe and loving home and education for the kids, Shelter must work hard to provide for the basic needs of its residents as well as to generate some much-needed income.

“The kids survive on rice and beans,” explained Hanna. “They buy the rice but then they grow the beans. They have some fields of cabbage and beets and things that they just sell… They have cows and they have chickens,” in order to be able to sell the eggs and beef.

“Food is everything. Your next meal is everything. That’s what they live for, is their next meal,” Hanna observed.

Muirvri seconds that observation.

“Taking care of 151 children requires a lot of both physical, human and emotional resources. Currently our needs revolve along sustainability for the home,” she said.

Adoption is seldom an option in Kenya due to a wide range of bureaucratic challenges. So Shelter Children’s Home works hard to prepare it’s residents for adult life by ensuring before the children exit the program: they have a college/university certificated, national identity cards and other legal documents “that they will need along their development journey. So they are ready to face the world,” said Muirvri.

She became the adopted mom of a newborn baby who had been found by Maasai tribe members in the woods near the orphanage. The baby was just hours old and his umbilical cord was still attached. Because Shelter was, at that time, not yet equipped to care for babies, Muirvri took the newborn to her house. She eventually adopted him, and he is now in 8th grade.

Like Muirvri, Hanna and Goolsby’s destinies are now also tied to Shelter.

“This is God’s way of showing me that this is where I can make a difference down the road, is helping her and these kids,” said Hanna. “Each one of them has a story, and it’s not good. But they can be good.”

Muirvri knows the first-hand benefits of helping these kids despite the personal cost to her.

“I derive my energy from seeing a child transformed from vulnerability to self-reliance. (Although) sometimes (my family) may not get what they need,” Muirvri said.

Besides working to meet their daily needs, Shelter Children’s Home is hoping to build what they are calling a sustainability center, a project conceived of by Goolsby and Hanna’s group. The facility would be a place to pack vegetable baskets, clean chickens, and store honey and onions, all for sale in local markets.

For more information, visit their Facebook page, Shelter Children’s Home, or hrstruehope.org.

Mary Wambui Muirvri, who took over running the Shelter Children’s Home from her grandmother in 2000. Mary

has made it her life’s work to provide a future for children who might otherwise live lives of neglect, abject poverty

and abuse.