California firefighters say there are similarities to Golden State

By LESLEE BASSMAN, Four Points News

Eric Garcia, who has lived off City Park Road for 15 years, said he was first attracted to the heavily-wooded area because of its natural beauty. But, on Wednesday, he took to neighborhood streets with fire fighting experts in an effort to become better educated on actions he and his family need to take to guard against what officials tout as an inevitable wildfire destined to strike the peaceful community.

“I live in a pretty remote area with lots of native (plants) around and that’s the one concern I have — a destructive fire,” Garcia said. “So, I’m trying to get smart about it and making sure we have everything taken care of to protect our home.”

Although he hasn’t taken any measures to date, he said the area “is getting continuously more and more dangerous,” citing the region’s recent hot summers.

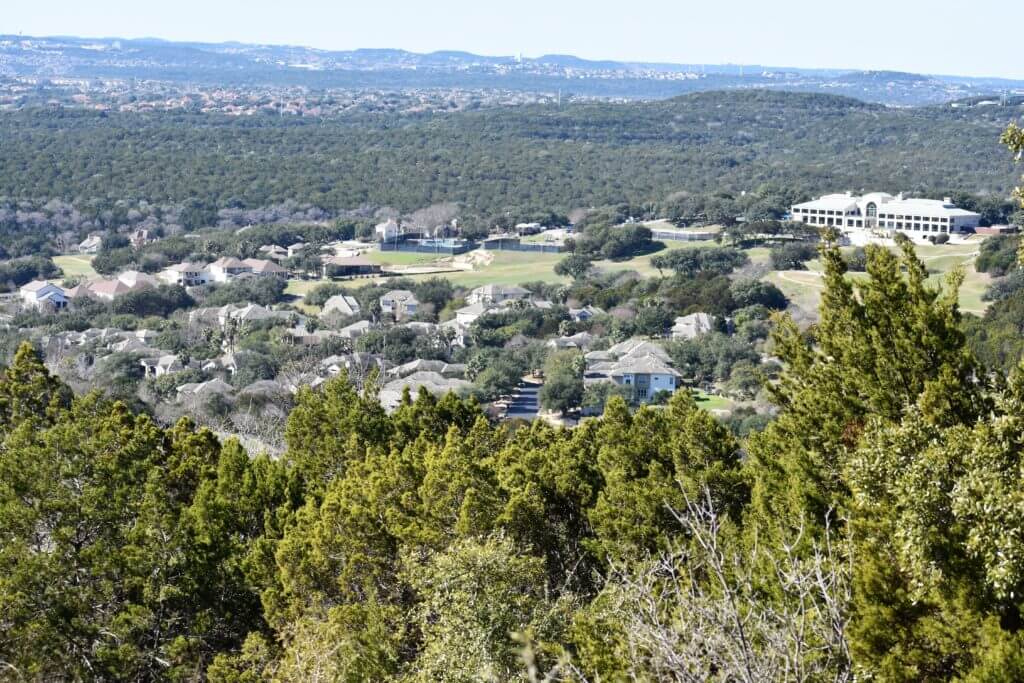

Randall Jamieson, River Place’s Firewise Coordinator, and Randy Denzer, secretary/treasurer with the Austin Firefighters Association, presented a two-day symposium with van tours that covered local areas that house the greatest risk of wildfire. They offered information as to what residents and communities can do to protect themselves. The program, held at River Place Country Club on Jan. 28-29, featured Bob Nicks, who heads up the AFA and is an Austin Fire Department battalion chief, along with two California firefighters, experts who managed recent major wildfires that struck the West Coast. City of Austin Council Members Alison Alter (District 10) and Jimmy Flannigan (District 6) also commented on city-wide efforts to safeguard residents against such natural disasters.

The meeting advanced ideas aimed at deterring the spread of wildfire in neighborhoods, proposals that go beyond individual homeowners voluntarily trimming trees and clearing brush.

Contemplating a wildland-urban interface code in Austin

Austin City Council is currently considering adopting a wildland-urban interface, or WUI, Code that would guide new construction in the face of increasing wildfire risks. A June 2019 report on the proposal stated that 61 percent of Austin structures and 67 percent of Travis County structures are located within the wildland-urban interface, with those structures harboring a greater risk of being impacted by a nearby wildfire than others farther away.

The code is slated to be finalized in March and the report states the cost to implement the program is $1.65 million.Specifically, a WUI Code can involve regulations governing hardening, or improving existing buildings and homes with ember-resistant materials on areas such as roofs, eaves, soffits and decks; choosing fire resistant products for new construction; having a plan for escape; and modifying wildfire fuels to create a defensible space that includes the first 30 feet of space around a structure.

Austin’s proposed WUI Code gives the Austin Fire Department authority to enforce the ordinance’s building construction and vegetation maintenance standards to structures in identified WUI areas within the city’s limits and limited purpose jurisdiction.

But Nicks said that such modifications and fuel mitigation should also be performed in community open spaces and wildlands as well.

“We can create a barrier around our homes, but if everything else continues to grow, it may overpower our barriers,” Nicks said. “So, a comprehensive code, in my opinion, is very important, not just for new construction.”

Noting the Four Points community is “fast-growing,” Nicks highlighted the need for continued firewise education of its residents and inspection of their homes.

California’s WUI codes are modeled after a national standard, with some counties increasing those standards and some cities adding more regulations, he said. Those provisions allow for citations to be issued for individuals or businesses not in compliance or provide for a government entity to bring the property into compliance and then seek compensation from the owner for the cost of doing so, he said.

“The spirit of those ordinances is to create that defensible space, and build, or create or replicate a hardened structure — fire resistant construction, clearances,” Nicks said. “Defensible space is great as long as everybody’s doing it.”

For Nicks, adding a WUI Code to a municipality is a way of enforcing and ensuring wildfire mitigation efforts exist within communities.

A call to action: Western TravCo mimics California’s wildfire risks

Former CalFire firefighter Todd Derum, who recently retired from the department as operations division chief for Sonoma County, found similarities between areas of California that witnessed catastrophic wildfires in the past few years and western Travis County. Those commonalities include wildland or flammable fuels set against homes, homes located in the WUI and neighborhoods with only a single accessway.

“So it’s fuel, weather, topography — that’s what drives wildfires,” he said. “You have hot temperatures. You have droughts (and) some winds. Wildland fuels of grass, brush, juniper are very explosive. And the topography, with a lot of homes built on ridges with beautiful views out the back but (dropping) down into wildland fuels.”

A December 2017 wildfire destroyed more than 1,000 structures and took the lives of one firefighter and 22 civilians around Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. An October 2017 wildfire around Santa Rosa, Calif., destroyed more than 5,600 structures, killing 22 residents.

Nicks cited a recent CoreLogic report that ranks Austin as fifth in the nation among similarly populated metropolitan areas that are most at risk for a major wildfire. CoreLogic focuses on risk assessment in the insurance industry.

“It’s time that we all take some responsibility and recognize that we’re at risk,” he said. “You don’t need two guys from CalFire to tell you that. You’re living it.”

Citing a parallel to Paradise, Calif.’s density — a community that witnessed a horrific wildfire in November 2018 — Denzer said the added density in that neighborhood was not addressed in terms of fire risk. Despite the community possessing three ways in and out, the wildfire killed 88 people, he said.

“So there’s a lot to be said about community refuge areas,” Denzer said of spots within communities that are considered safe for residents during a wildfire. “In Paradise, there’s a good chance that if they had put everybody in a parking lot, they would have been miserable, had some smoke inhalation but they might be here today.”

The golf course at River Place Country Club has been viewed as such an area.

A new 42-acre development proposed for the end of Milky Way Drive — a road with only one accessway off River Place Boulevard — presents wildfire evacuation issues for the neighborhood’s 4,000 residents. The residential project is slated for the top of a plateau in the city’s wildland-urban interface. In the fall, Austin City Council approved rezoning the tract to allow for the development of high density townhomes and condominiums as opposed to the 25 single family homes already existing on the developed portion of the roadway that are sized at more than one acre.

Jamieson called the zoning case “precedent setting” since he said the situation permitted a project’s density to be increased without regard to wildfire risks.

“This piece of property is the highest elevation in the city of Austin and it is one of the highest wildfire risk areas in the city,” Jamieson said of the tract.

During a tour of River Place’s Milky Way neighborhood, Denzer said a combination of wildfire fuels, site slope and the state’s normal drought cycle makes the parcel even more vulnerable.

Jamieson said a 28-acre parcel of land that just came up for sale in Long Canyon presents similar issues since the listing price of $6.2 million indicates it may be developed as high-density condominiums.

“It is dead center of a one-way in (and) one-way out canyon,” he said of the Long Canyon tract.

Fuel mitigation issues in Four Points

Adding a shaded fuel break in the area trims trees up six feet; however, cedar trees in the Four Points area have heights of more than 20 to 25 feet tall, Nicks said. Although shaded fuel breaks reduce the frequency of fires, such a project around River Place “would create a false sense of security” since a wildfire can jump tree tops, he said.

“It looks nicer but you’re partially mitigating the situation because, realistically, a fire that’s moving through the crowns — anywhere I’ve seen here today — if we had a fire coming, we’re in big trouble,” Nicks said of adding a shaded fuel break in River Place.

Dave Russell, CalFire deputy chief of operations, said fuel mitigation is important since wildfires can be devastating, even in smaller doses.

“It doesn’t need to be a 200,000-acre fire (to exact damage),” Russell said. “It could be the 100-acre, 80-acre Steiner Ranch fire that impacts the different homes and displaces and evacuates citizens during that event.”

City leaders comment on safeguards against wildfire disasters in Part II in next week’s edition.