By LESLEE BASSMAN, Four Points News

Volente resident and business owner Frank Wolfe said he’s very worried about the potential for water contamination or structural damage to his home should a regional water agency continue on its current course to build an underground intake pipeline and tunnel through his community.

“We put everything we had into this house,” he said of his Sherman Street home that boasts a lake view from its top floor. “Living over here in Volente is kind of above our pay grade but we managed to get a house and we put a lot of money into it. We want this to be a great community.”

Although he’s lived in the village for only a year, the pending Brushy Creek Regional Utility Authority project has been an issue for Volente for years before he moved to the area.

Construction on the proposed project is to begin in 2022 and wrap up in 2027 with an estimated price tag of some $180 million.

Some residents have voiced concern the project will cause traffic congestion from construction vehicles and possibly create damage to the fragile wells used by all residents of the lakeside municipality as their water supply.

But the BCRUA is of a different opinion and its representative maintains the project is essential to the growing region.

A bit of history

The Brushy Creek Regional Utility Authority or BCRUA was formed in 2007 as a regional partnership between the cities of Cedar Park, Leander and Round Rock. Its purpose was to extract water from the Highland Lakes for the future needs of the expanding communities, said Karen Bondy, BCRUA general manager.

The group built a regional water plant and floating raw water intake on Lake Travis. That intake — sandwiched between Cedar Park’s and Leander’s pre-existing floating raw water intakes which served other water treatment plants — serves all three cities. The combination of the area’s large population growth and the drought of 2011-2012 caused lowered water levels in the intake. Soon after, the cities determined that not only did they need more capacity for the future but they needed to drought-proof their vital water supply.

Part of the long-term plan for those fast-growing cities included putting a deep water intake into the lake that could serve those communities, Bondy said.

“That’s where Volente came in,” she said.

Between 2008 and 2012, the agency evaluated eight potential locations to base the deep water intake and eventually decided upon Volente as the best site for the project that included underwater piping and, at the time, an open-cut trench traversing through much of the community, infrastructure that would get the water from the pump station to the water treatment plant, Bondy said.

“We were the closest point to pull (water) out of Lake Travis,” Volente City Council Member Judy Barrick said.

However, town officials opposed the trench, resulting in an October 2012 memorandum of understanding signed by representatives from all three cities, the BCRUA, and the village, Bondy said. That agreement not only moved the pump station out of Volente, lessening the project’s impact on citizens, but also replaced the proposed trench with a tunnel sunk deep below the surface. According to Bondy, the cost of those changes was about $15 million.

“They were trying to figure out what was best for them and for us,” Barrick said. “This has been going back and forth for several years.”

The project

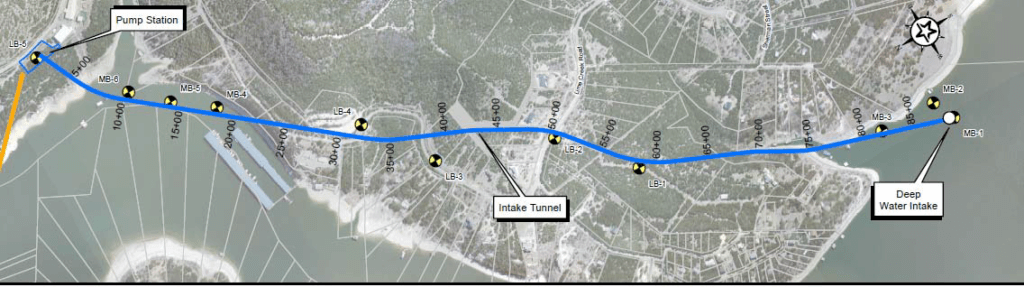

After negotiations concluded between the BCRUA and the village, Volente was left with an intake pipe deployed underwater connecting to a below-ground tunnel and a 3,000-square-foot maintenance building to be constructed on a BCRUA-owned lot at 16621 Jackson St., Bondy said. The BCRUA has acquired easements for the properties covering the tunnel, she said.

Diagrams of the proposed tunnel profile and the overall plan were presented at a 2017 community meeting in Volente, Bondy said. At the edge of Lake Travis, the tunnel is almost 200 feet deep and then sinks to more than 400 feet deep through Volente, she said.

Most of the time, when the lake is up, the water intake portion of the project will be underwater, Bondy said. It is planned to be surrounded by buoys to protect it from boats interfering with the project and potentially contaminating the supply with oil or gas, Bondy said. When the lake is very low, an intake screen may be visible but only from the edge of Volente’s cliffside, she said.

The approximately $180 million project is anticipated to begin in mid-2022 and expected to be completed before the summer of 2027 since the added water capacity will be needed before the summer of 2028 to accommodate the extra growth in the area, Bondy said. The BCRUA will seek a loan from the Texas Water Development Board in the spring to partially fund the project, with the cities of Cedar Park, Leander and Round Rock kicking in the rest of the costs, she said.

Source of contention

Bondy said the project is expected to serve up to 500,000 people when finished.

“This project is really important to the regional economy,” she said. “These cities are growing like crazy and they need future water to be able to maintain the health of their communities — public health, economic health. Water is fundamental.”

Although Volente won’t bear any costs for the project, its residents may not reap any of its benefits either. And that includes tapping into a public water system that’s currently missing from the community.

Since private wells serve as the municipality’s water source, Bondy said a September draft interlocal agreement between the village and the BCRUA — its third version — leaves open “that if Volente is interested in getting water from the project, we would agree to consider if that’s what Volente determines that’s what they are agreeing to do.”

“There’s no guarantee,” Barrick said of a public water supply. “We have 600 homes out here that could benefit if we were able to have some infrastructure or if we were able to get some money from them to be able to do an infrastructure to tie into that.”

Once the project is done, Bondy said the water flowing within Volente won’t be treated but, instead, just raw water from the lake. With the water treatment plant located near Cedar Park and Leander, Bondy said the water would need to travel from the lake to those cities and then back to Volente through the treated water pipeline for the community to access it as its drinking supply.

“A lot needs to be looked into to determine if that’s what they want to do,” she said of the supplemental pipeline and infrastructure needed.

Similar to Wolfe, Barrick said she feared the local wells will be disturbed in the process, citing the latest draft of the proposed agreement with BCRUA deletes a prior insurance provision.

“So we’re very concerned about what’s going to happen to those wells when (the BCRUA) starts tunneling and drilling,” she said.

The risk is even greater for residents on the side of the village living near the planned major boring sites, Barrick said.

“The BCRUA has always recognized the importance of the private, domestic groundwater wells in Volente and established a groundwater well monitoring program several years ago to proactively categorize and identify groundwater wells,” Bondy said. The program includes an inventory of groundwater wells within 400 feet on either side of the proposed tunnel. The BCRUA contacted well owners to let the agency collect water level and quality data on those wells to compare with the water level and quality during the project. Some residents agreed to the data collection but some didn’t.

Last year, the Volente Council approved permits for the BCRUA to drill four wells to monitor the water quality and levels in the Lime Creek Road right of way, but then didn’t issue permits for the agency to do so, Bondy said. Currently, none of those baseline monitoring wells are in place, she said.

“What we decided to do is we are getting easements from private landowners to do those groundwater wells,” Bondy said. “We still want to have a good baseline because it is still, obviously, a concern to the citizens of Volente and we want to have good data.”

Because the BCRUA was able to work out an agreement with private landowners to create monitoring wells, Barrick said the agency didn’t need the four wells approved by Council in 2019.

Village leaders want to have an interlocal agreement that protects its residents in the five to seven year project, she said. They recognized the need to keep local roads safe and address the added project traffic — gravel trucks and cranes — coming down Anderson Mill Road to Lime Creek Road, a route that harbors severe turns, Barrick said. With only one way in or out of the hamlet, residents could be stranded should traffic back up for a vehicular incident.

To lessen the potential for traffic buildup, the BCRUA agreed to tunnel from only one direction so as to minimize the truck use related to the tunneling and materials coming out of the tunnel, Bondy said. That measure added to the timeframe for the project, she said.

Typically on a project such as this one, Bondy said, the contractor would name the village as the additional “insured” on that contract, an action the BCRUA can accommodate.

“We can do that,” Bondy said. “We’re not saying we won’t do that. It was highly unusual what Volente was asking for.”

What now?

Bondy said the MOU of 2012 lays out the tenets of how its parties would work together “in good faith,” with the BCRUA relocating the pump station out of Volente and using a tunnel pipeline. In return, she said Volente agreed to drop its objections to the project and “to apply reasonable planning and zoning requirements for all BCRUA construction in the village.”

Bondy said the agency will move forward based on the MOU but does have the power of eminent domain to proceed with the project.

According to Barrick, the property owned by the BCRUA must be rezoned for the agency’s intended project use, part of the ongoing process that not only includes permits but also producing and reviewing other applications, site development and tree removal. She said COVID-19 has slowed down this process.

“We’re still working with Volente,” Bondy said of the town hall meeting, planning commission and city council sessions that have occurred regarding the project. “I do believe that Volente is working towards a mutually agreeable (interlocal agreement) as we are.”

Barrick echoed Bondy’s assessment of the situation.

“How we can work with (the BCRUA) has been the big issue,” Barrick said. “How do we work with them and yet take care of the village and make sure that five or ten years down the road, we don’t have issues with drilling, boring, channeling and tunneling? So, that’s where we are right now, trying to come up with an agreement that works for both parties and so far we’re still in negotiations with them.”

BCRUA representatives have spoken with the village’s attorney but Bondy said she hopes her agency can get a dialogue going soon to address residents’ interests. As it stands now, she said the agency is waiting to hear back from its leaders after sending over a draft agreement last month.

“We’re just waiting,” Bondy said.

According to the village of Volente’s website, the City Council hosted two town hall events focused on the interlocal agreement proposed between the village and the BCRUA on Oct. 23 and Oct. 24. For more information please go to www.villageofvolente-tx.gov.