By LYNETTE HAALAND, Four Points News

A longtime Grandview Hills resident hand-painted Ukrainian Easter eggs and sold them over the Easter holiday weekend to raise money for relief.

“The decorating of pysanky is considered one of the ways to show that Ukrainian culture exists at a time when the invasion of Russia threatens to destroy Ukrainian culture and heritage,” Marian Evoniuk said.

She and her husband Chris were the first people to purchase a lot in Grandview Hills back in 1988, almost 34 years ago when it was called The Parke.

Evoniuk painted 40 pysanky and depending on the design, each egg took between 2.5 to 8 hours to complete.

Earlier this year she found a humanitarian cause to create the special eggs for. Then she said she “just hoped and prayed that people would like my pysanky enough to purchase them. The results were humbling.”

Evoniuk set up at the Grandview community event on April 16 and sold all but seven, raising over $1000 thanks to her wonderful neighbors and friends, she said.

The funds will go to Good Bread, which she found is a worthy cause doing great things.

Before the war, Good Bread would deliver goodies to people with mental and intellectual disabilities like autism and Down syndrome, and give some a chance to work in their bakery.

“Now with the war raging on, they bake and distribute, free of charge, between 400 and 800 loaves of bread as well as cupcakes and cookies every day to the elderly, the children, the Ukrainian military and volunteers, hospital patients, to the people in bomb shelters and to anyone who is without food in Kyiv,” she shared.

More information on Good Bread can be found at https://eng.goodbread.com.ua

Evoniuk learned to create pysanky when she was 10 years old. It was part of the Ukrainian culture she was raised with in rural Saskatchewan, Canada.

“My mother was 2-weeks-old when my grandparents fled Ukraine from Russian oppression during the early 1900’s,” she shared. “My father was born a first-generation Ukrainian Canadian, so my Ukrainian roots run deep. Even though I’ve never personally visited Ukraine, there’s a strong feeling of solidarity with its people. It’s my motherland so to speak.”

Her husband Chris, also a Ukrainian, supported her and helped her stay focused on her goal while making the Easter eggs.

The process is complex. Delicate lines and shapes are composed on an egg with warm wax, usually beeswax, dispensed from a stylus-like tool called a kistka, she explained. The egg is then soaked in a light-colored dye, for example yellow, and the designs that are to remain yellow are covered in wax. The process is repeated with gradually darker dye colors and more wax coverings until the layers are complete.

“For pysanka artists throughout the world, the exercise can be an emotional experience, with thoughts turning to the suffering in Ukraine,” Evoniuk shared.

This year, many artists decided to sell their Easter eggs to raise money for humanitarian efforts in Ukraine.

“The efforts of many can make a difference,” Evoniuk said. “Decorating eggs has become a gesture of peace with messages of hope and prayers that Ukraine will prevail.”

BONUS coverage: History of pysanka by Marian Evoniuk

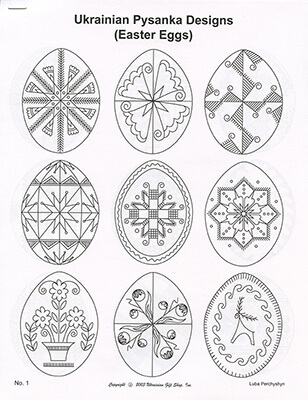

The Ukrainian Easter Egg, also known as a pysanka, is an art form derived from the verb “pysaty”, meaning “to write” and dates back to pagan times where, according to folk tales, Ukrainians worshipped the sun. It warmed the earth and therefore was a source of life. Eggs decorated with symbols of nature were chosen for spring rituals because they were believed to have powers that would bring fertility and good harvests. This was partly due to the eggs still having life inside of them. With the acceptance of Christianity in 988, the symbols came to represent Christ’s Resurrection and the Holy Trinity. Every symbol, design and color on a pysanka bears traditional meaning and significance and often includes a hope or wish for the future.

According to ancient pre-Christian legend, decorating pysanky is meant to ward off evil. In the Carpathian Mountains, the legend tells the story of a monster, the personification of evil, shackled to a cliff. Each pysanka creates another link in the chain that binds him. In that story, the more pysanky that are made, the tighter the chains are wrapped around the monster, keeping it at bay so that it doesn’t destroy the world.

While symbols, designs and colors can be open to interpretation, there are some commonly held beliefs. Red is traditionally used for passion, hope and blood, white for innocence and purity, and green for rebirth. Black is for eternity and for Ukraine’s soil which is fertile and gives Ukraine its fame for being the bread basket of the world. Triangles represent the Holy Trinity while the egg itself is a symbol for Christ’s resurrection. Netting designs symbolize protection from evil. Meandering triangles are known as wolf’s teeth and signify fierce protection. Eight-pointed stars are a symbol of the sun, the giver of life. White stars radiate peace, hope and energy. The cross holds two meanings: the sun’s victory over darkness and a cross of suffering and resurrection. The poppy is a symbol to remember those who died in military service. An embroidered cloth called a “rushnyk” is traditionally used to celebrate a child’s birth, a wedding or to accompany soldiers.

The eggs are a demonstration of patience and care, upon which intricate designs are written rather than painted. Depending on the design, each egg takes 2 ½ to 8 hours to complete. Delicate lines and shapes are composed on a raw egg with warm wax, usually beeswax, dispensed from a stylus-like tool called a kistka. The egg is then soaked in a light-colored dye, for example yellow, and the designs that are to remain yellow are covered in wax. The process is repeated with gradually darker dye colors and more wax coverings until the layers are complete. The wax prevents the dyes from covering the designs. Once complete, the wax is melted either by candle flame or in a 200 degree oven and wiped off to reveal the beautiful pattern underneath. To preserve the pysanka, clear varnish is applied and the inside of the egg is either blown out or the egg is left raw to dry out over time. The pysanky will last indefinitely, unless dropped or damaged. Also keeping them out of direct sunlight will prevent the colors from fading.